Over evolutionary time, organisms have had to evolve ways to cope with varying oxygen levels. Hypoxia inducible factor, HIF, is the primary way our bodies respond to changes in oxygen availability.

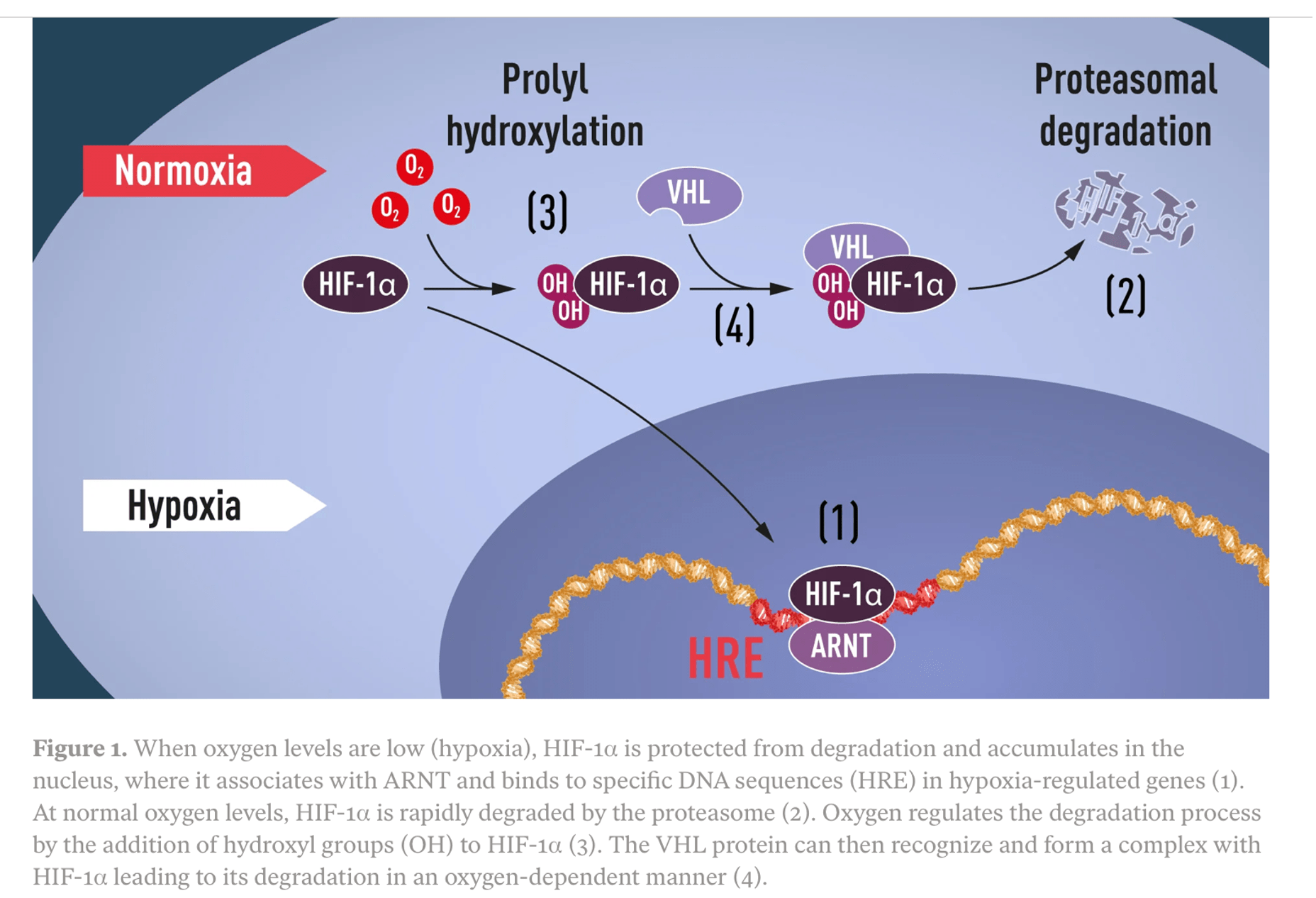

HIF-1 alpha is stabilized during hypoxia, allowing it to reach the cell nucleus and alter the expression of hypoxia related genes.When oxygen tension is higher, HIF is degraded by a mechanism involving the VHL protein and delivery to the proteasome.

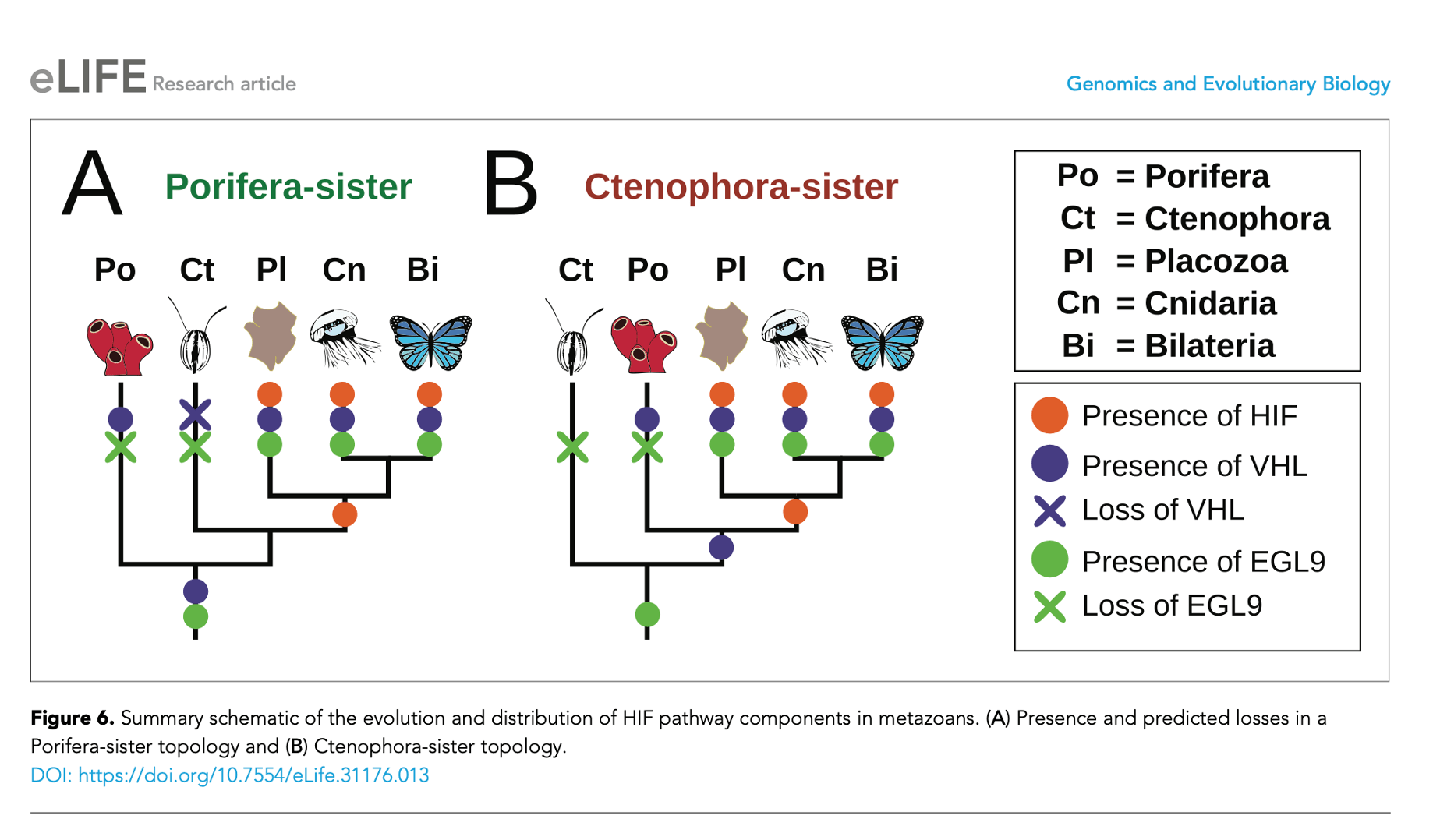

Hypoxia inducible factors have been around a long time, suggesting that it is adaptive to change one’s internal state in response to oxygen. HIF proteins evolved in an early metazoan ancestor 600-700 million years ago.

We don’t share HIF with sponges, but oxygen sensing molecules EGL9 and VHL evolved in a more distant evolutionary ancestor that gave rise to tunicates and sponges and humans. This evolutionary legacy implies that durable and powerful selection maintained the capacity to sense and respond to oxygen. In fact, efforts to create genetic knock-out mice without HIF show that HIF is necessary for life. The knockouts uniformly die in utero.

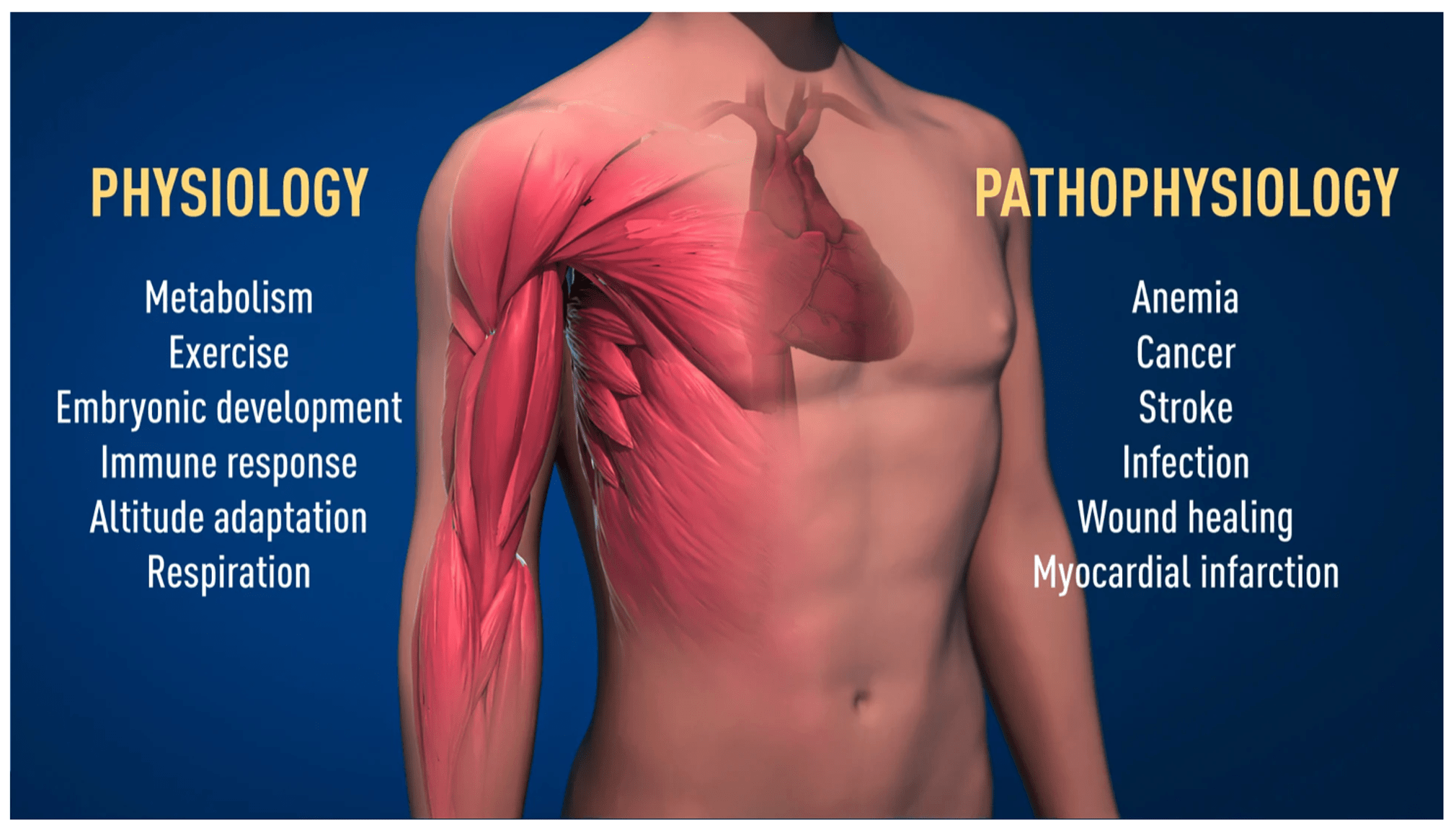

So what does HIF do that is so important? In addition to orchestrating immune responses, which we covered in the previous post, HIF changes gene expression involved in blood cell production, blood vessel growth, blood circulation, metabolism, response to exercise, and altitude acclimatization. The researchers who figured this out were awarded a Nobel prize in 2019. This image showing HIF involvement in health and disease is from Nobelprize.org:

HIF is also implicated in diseases, including acute mountain sickness. At Taos ski valley in my state of New Mexico, an on site medical clinic diagnoses some individuals with headache, GI symptoms and shortness of breath. These unhappy would-be skiers have acute mountain sickness or high altitude pulmonary edema. After treatment with oxygen and delivery of oxygen tanks to their hotel room, they are often able to continue their ski vacations. Other individuals appear to tolerate hypoxia well at ski areas at high altitude in the Rocky Mountains. Many skiers perform complex athletic tasks at altitude while having oxygen saturations that would cause alarm in the emergency department. We have measured oxygen saturations in the 70s and 80s in healthy volunteers at 3500 meters in Taos. In addition, some highly trained athletes at sea level experience hypoxia while exercising. Healthy people also tolerate hypoxia during normal sleep, especially during REM sleep. The explanation of hypoxia during REM is a decreased hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) compared to the wakeful state.

Tibetans and other high altitude groups in the Himalayan plateau get along well with hypoxemia at altitude, showing reduced susceptibility to acute mountain sickness and improved capacity for physical exercise at high altitude. These groups have specific genetic changes that permit adaptation to high altitude hypoxia. Anthropologist Cynthia Beall identified a mutation in the gene EPAS-1, also known as HIF-2 alpha, that showed evidence of positive selection in Tibetans. The EPAS-1 variant under positive selection had the functional effect of blunting erythropoiesis from hypoxia. As a result, the levels of hemoglobin in the high altitude Tibetans can resemble that measured in people at sea level. Relatively lower hemoglobin at high altitude benefits carriers of the allele by lowering the risk of chronic mountain sickness. Reduced function of EPAS-1 in the umbilical cord also may increase blood flow to the fetus during pregnancy. As a consequence, Tibetans are protected from intrauterine growth retardation and have higher birth weights on average. This indicates a fitness advantage for the altitude related variant. Further evidence for the adaptiveness of variant EPAS-1 is the observation that most hypoxia-tolerant high-altitude mammal and bird species do not have elevated levels of hemoglobin.

To wrap up, Tibetan highlanders cope well with chronic hypoxia, and genetic lowlanders (the majority of us) generally tolerate episodic hypoxia. This suggests HIF responses to hypoxia tend to be adaptive in the environment in which it evolved. Among lowlanders, HIF generally works well and buffers individuals from sources of hypoxia that are commonly encountered at sea level. In Tibetans, naturally-selected variant HIF-2 alpha permits adaptation to the hypobaric (low atmospheric pressure) hypoxia at altitude. When newcomers to altitude ascend too high and too rapidly, maladaptive acute mountain sickness (AMS) is the result. AMS seen in skiers at Taos can be understood as an evolutionary mismatch. AMS resolves with supplemental oxygen or descent to lower elevation with higher oxygen partial pressure. These diseases highlight tradeoffs in the regulation of HIFs and shed light on its evolution in humans.

Categories: Uncategorized

Joe Alcock

Emergency Physician, Educator, Researcher, interested in the microbiome, evolution, and medicine

Figure 1 clearly and simply depicts the workings of HIF. What is the source?

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2019/press-release/