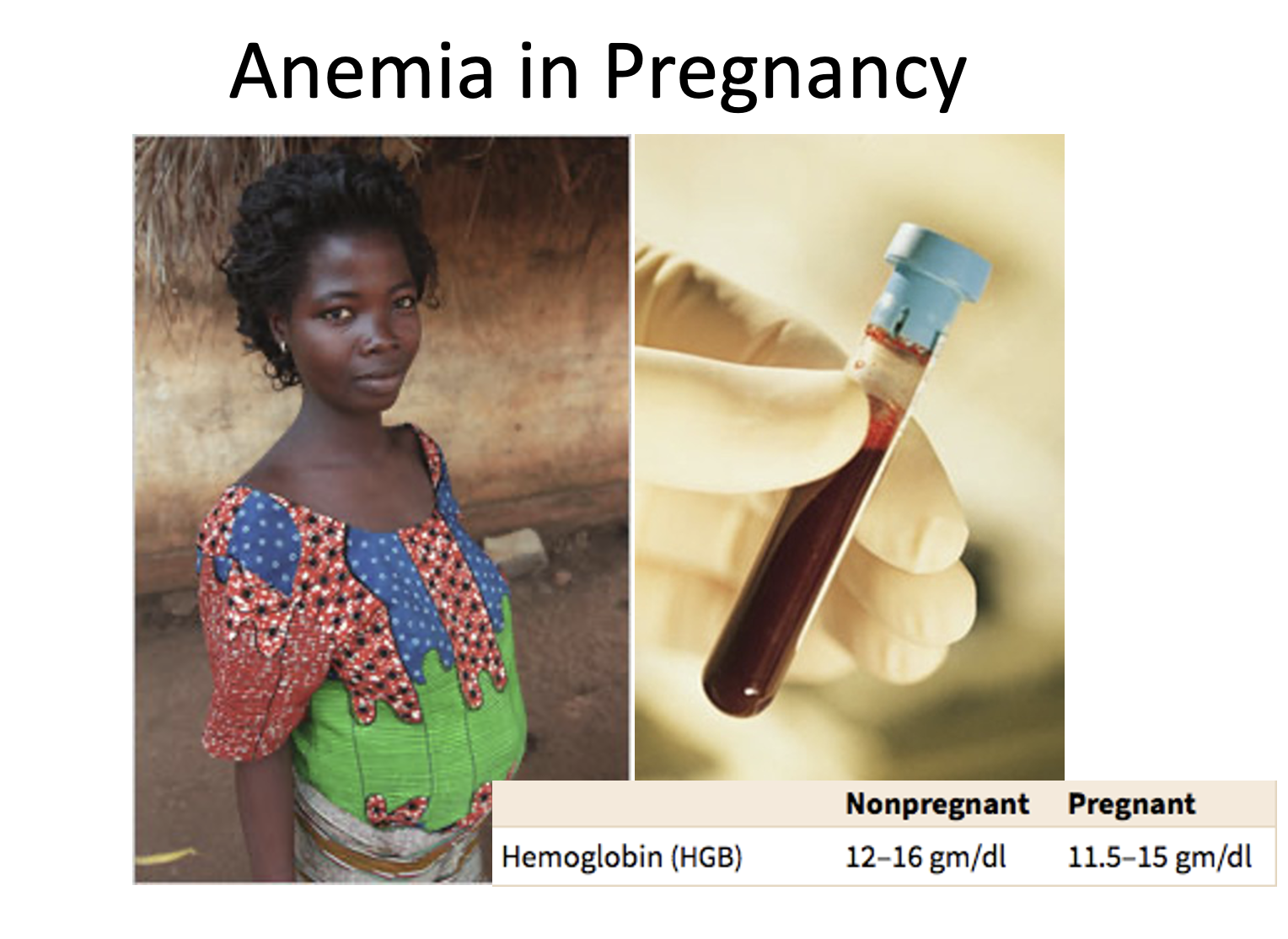

Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy is common. Should it be treated?

Hemoglobin during pregnancy is lower than in the non-pregnant state. As compared to pre-pregnant levels, hemoglobin is decreased by approximately 1g/dL in the second trimester. Hemoglobin declines by another 1g/dL in the third trimester. As Sifakis and Pharmakides write: “moderate iron deficiency does not appear to cause a significant effect on fetal hemoglobin concentration. An Hb level of 11 g/dl in the late first trimester and also of 10 g/dl in the second and third trimesters are suggested as lower limits for Hb concentration.” In other words, lower than “normal” hemoglobin is a typical and expected finding during pregnancy. In line with that notion, some studies have shown worse pregnancy and fetal outcomes with giving iron to women who have normal iron stores. In addition, higher than normal hemoglobin has been associated with poor fetal outcomes.

Hemodilution is partly to blame for decreased hemoglobin during pregnancy. Intravascular volume expands more than red blood cells in pregnancy, leading to reduced hemoglobin, iron and ferritin concentration. In other words, because of volume expansion, red blood cell concentration and iron stores seem lower than they are. However, low hemoglobin is also caused in part by blunted erythropoietin production, which is low relative to the degree of anemia in each trimester of pregnancy. Decreased erythropoietin usually disappears after delivery, and hemoglobin levels increase to pre-pregnancy levels.

The bottom line: Relative anemia during pregnancy appears to be a regulated phenomenon, a consequence of natural selection acting on iron metabolism, transport and storage. It is not necessarily a disease. Mild to moderate anemia in pregnancy should be considered normal during pregnancy, and often does not need intervention. On the other hand, severe anemia, especially a hemoglobin of 6g/dl or lower, is associated with very poor fetal outcomes. In that scenario, most experts recommend treatment.

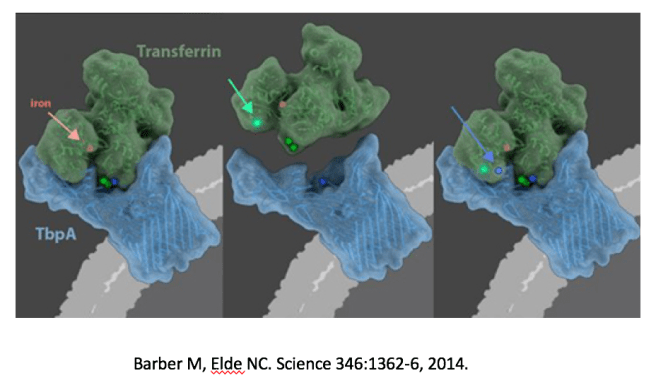

Why did apparent anemia in pregnancy evolve? One clue is that iron sequestration is increased in early pregnancy, with transferrin that progressively increases in pregnancy. Transferrin is a host iron transport protein that is the focus of intense and ongoing host pathogen co-evolution.

Matthew Barber and colleagues showed that humans have a long co-evolutionary history of competition with pathogens over free iron. Neisseria meningitidis, for instance, shows evidence of ongoing selection over its iron binding protein TbpA. TbpA is involved in iron piracy that steals iron from host transferrin, the host iron transport protein. In 2015, Barber was awarded the Omenn prize for this groundbreaking work at the ISEMPH conference on evolution and medicine.

Thus, increased iron sequestration during pregnancy might represent a protective feature that prevents infection, since many pathogens use iron is a necessary co-factor for growth and virulence. Transferrin bound iron is also the predominant way that the fetus takes up iron. Placental transferrin receptor 1 and fetal hepcidin promote iron transport across the placenta.

It is also possible that conflict over iron provisioning exists between fetus and mother. Iron is important in fetal growth, and evidence for fetal-maternal conflict exists for many other traits that regulate fetal growth. Examples include glucose and the imprinted insulin like growth factor IGF-2. Other sequelae of maternal-fetal conflict, such as gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia are associated with decreased iron provisioning to the fetus. Placental hypertrophy is associated with maternal anemia, providing evidence for fetal control over iron delivery. Supporting the concept of conflict over iron, a paternally imprinted gene in mice encodes a protein that has been shown to have profound effects on iron transport in the placenta. It is uncertain whether similarly imprinted genes regulating iron homeostasis exist in humans. If they do exist, paternally imprinted genes might promote fetal iron delivery and maternally imprinted genes would be expected to resist that transfer. This prediction relies on previous findings that imprinted genes have opposing effects on fetal provisioning.

Some apparent iron “deficiency” anemia during pregnancy may not represent a deficiency in the traditional sense. Competition with pathogens, and potential maternal-fetal conflicts of interest in pregnancy could play a role in iron trafficking during pregnancy. This is an area needing more study. However, an evolutionary medicine perspective seems to favor a “less is more” approach to treating mild anemia in pregnancy.

Caveat: It remains standard of care to provide daily oral iron and folate during pregnancy. Remember, this blog is not medical advice.

Categories: Uncategorized

Joe Alcock

Emergency Physician, Educator, Researcher, interested in the microbiome, evolution, and medicine

Our understanding of this topic could be advanced with separate measures of plasma volume and hemoglobin mass (not hemoglobin concentration) throughout pregnancy. If the lower hb is simply a result of hemodilution, then follow up “why” questions might be different.

Great comments Cynthia. One lesson is: we shouldn’t worry about anemia if it doesn’t exist. A second lesson is that there are under appreciated costs to boosting iron status generally, and in pregnancy too. A third lesson is that this is complicated – it is hard to measure iron status in pregnancy because of all these cross currents – hemoglobin and ferritin both are problematic proxies for a variety of reasons.

Just asked elicit ai for relevant information. There isn’t much. Here’s the summary.

Studies report that hemoglobin mass—that is, the red cell or erythrocyte mass—rises during pregnancy relative to the non‐pregnant state. For example, several studies indicate a 15–25% increase in red cell mass by term. One study noted a 100‐ml reduction at 12 weeks followed by a net increase of 180 ml at 36 weeks, while another reported an 18% (250-ml) increase without iron supplementation that grew to 400–450 ml when supplements were provided. In each study, plasma volume expanded by 25–50%, eclipsing the increase in hemoglobin mass. These quantitative findings document a measurable upregulation of erythropoiesis during pregnancy.

And here’s the link to more information.

Even if overall hemoglobin volume is increased during pregnancy, it is possible that the reduced concentration of hemoglobin per unit volume – resulting from plasma expansion – reduces the risk of infection by iron-sensitive pathogens. I could not find a reference that tests this specifically in pregnancy. The prediction is that blood form second and third trimester pregnancy would be resistant to in infection in vitro (and in vivo). Changes in iron-related acute phase proteins might confound the picture. Two studies support this idea, though. A 2020 paper – Hemoglobin stimulates vigorous growth of Streptococcus pneumoniae implies that lower hemoglobin would be protective by inhibiting pathogen growth and virulence. Higher hemoglobin also increases Mycobacterial growth in vitro and is associated with a greater risk for tuberculosis in vivo. That has obvious implications for high altitude people. Did attenuated hypoxic erythropoiesis in Tibetans with variant EPAS1 evolve in part because of selection from TB?

Responding to your questions “Did attenuated hypoxic erythropoiesis in Tibetans with variant EPAS1 evolve in part because of selection from TB?” Hmmmm…

The EPAS1 haplotype of Tibetans came from the Denisovans living in in Siberia about 50,000 years ago. As far as I know, the published articles on Denisovans do not mention signals of selection in that population at that time. Frequently replicated evidence of very strong signals of selection in Tibetan Plateau samples along with an altitude gradient in allele frequency argue that hypoxia was the agent of selection.

Looking for evidence of the antiquity of TB, here is the clearest statement I found. “Of special note is the fact that all new models are in broad agreement that human TB predated that in other animals, including cattle and other domesticates, and that this disease originated at least 35,000 years ago and probably closer to 2.6 million years ago. ” Stone AC, Wilbur AK, Buikstra JE, Roberts CA. Tuberculosis and leprosy in perspective. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2009;140 Suppl 49:66-94. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21185. PMID: 19890861. It is possible that the earliest migrants to the Tibetan Plateau took TB with them. I don’t know if it is probable.

On the other hand, Steve Corbett has argued that Tibetan EPAS1 variants make Nepali migrants to Australia (some of whom have Tibetan ancestry) particularly vulnerable to TB at low altitude. Corbett S, Cho JG, Ulbricht E, Sintchenko V. Migration and descent, adaptations to altitude and tuberculosis in Nepalis and Tibetans. Evol Med Public Health. 2022 Mar 8;10(1):189-201. doi: 10.1093/emph/eoac008. PMID: 35528702; PMCID: PMC9071402.

We have generated some research ideas for pregnancy and anemia and for EPAS1 and infectious disease.