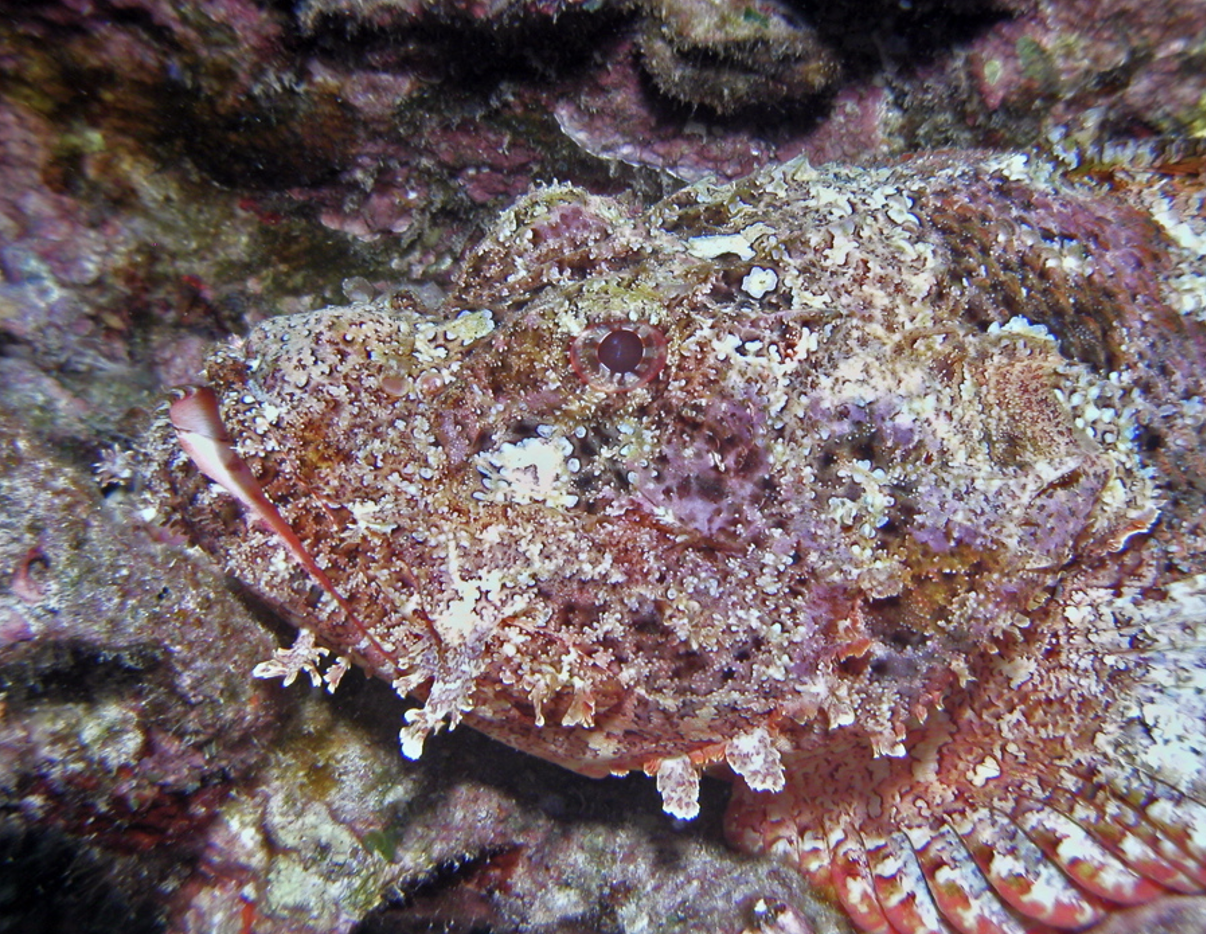

In the early 2000s I went on one of many epic fishing expeditions to Baja California with my good buddies Roland and Greg. Although our main target was dorado (mahi-mahi), I spent one afternoon fishing for reef fish with Greg. Our hooks spooled out, and within a few minutes we had fish on the line. I pulled up a colorful fish with an enormous head.

“Be careful with that one,” Greg said. That’s a scorpionfish and it can sting you, but it’s good eating,” he continued. I held the fish in front of me, dangling from the line. I tried to negotiate a pair of pliers towards the fish’s mouth. Before I could react, I felt pain. The animal swung its body over its head and stabbed me in the right hand. “It feels like a bee-sting,” Greg tried to reassure me. Worse than a bee sting, I thought, as the burning intensified. I set my fishing rod aside while my excited companions kept pulling up fish. They were not in the mood to head to shore. I plunged my hand in ice cold water in the cooler and got a bit of relief when my extremity went numb. Worryingly, the pain appeared higher up on my arm, near my biceps, traveling towards my armpit. What, I wondered, would happen when the pain got to my heart?

Some time later, enough fish were collected and we returned to camp where Roland was relaxing in a beach chair. He put down his Pacifico long enough to tell me that I should heat up some water and plunge my burning hand into it. That seemed counterintuitive at best. After a brief protest, I followed Roland’s orders. The pain subsided after the hot water treatment, but not entirely. Besides pain, the venom had done damage in the hours since the sting. My hand swelled like a balloon. I pressed my finger into my wrist and left a deep dent in the skin. We learn in medical school that pitting edema (usually involving the legs) is a sign of congestive heart failure. My heart was okay, but I had pitting edema on my forearm. It lasted for weeks.

A few years later, I was the victim of a small stingray while surfing at Coronado beach in San Diego. Stingrays have a bony barb that is bathed in venom. Stingrays will offer you a sample of that venom if you step on them in shallow water. This time I was wiser than when I had encountered the scorpionfish. I returned to the condo and heated water in a large pot. The pain disappeared after a hot soak.

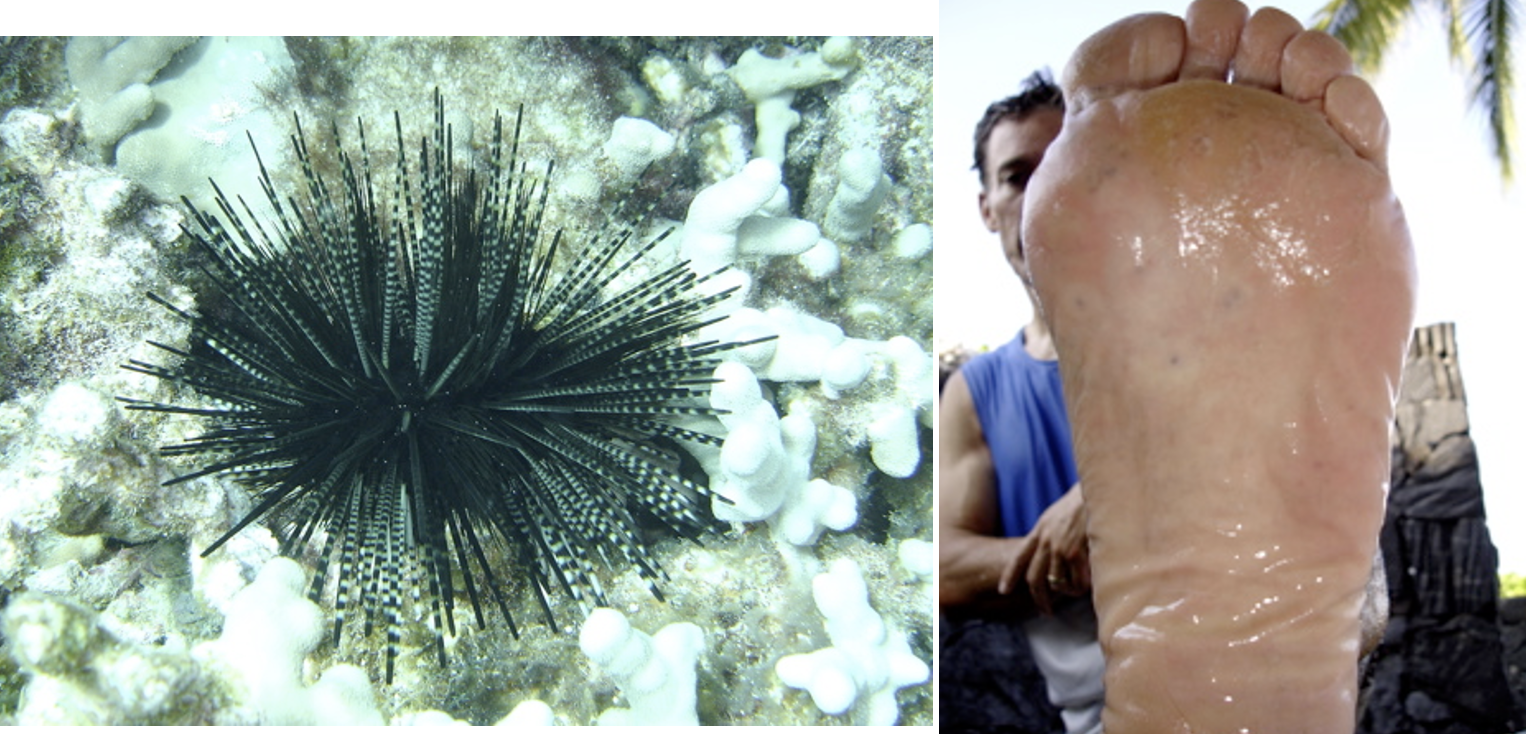

I lecture medical students at the University of New Mexico about venomous marine animals. I tell them that hot water immersion is the appropriate treatment for the venoms of bony fish, including my scorpionfish nemesis and the stingray. Hot water treatment of pain also works for marine invertebrates, including nematocyst stings of Physalia, the Portuguese man ‘o war. My colleague Darryl Macias had an opportunity to try hot water treatment for another invertebrate, the sea urchin. An urchin on the island of Hawai’i punctured Darryl’s foot. A hot water shower relieved the pain.

Using hot water to counteract pain was first described by German fisherman in 1758. One reason for hot water immersion’s effectiveness, I first learned, was that marine venoms are heat labile, and could be deactivated with sufficient heat. Others have reasonably pointed out that for this to work, the water would be so hot that it would denature the proteins in your body, resulting in tissue necrosis. To avoid thermal injury, the recommended temperature is “hot but non-scalding.” An alternate explanation is the gate-theory of pain. When pain neurons are triggered, the signal must pass through a “gate” in the spinal cord before it reaches the brain and is perceived as pain. Gate theory suggests that signals conveyed by parallel neurons can shut the gate. This might explain why rubbing a injury can sometimes relieve pain.

However, this is not why hot water immersion works. Hot water acts on a specific peripheral pain receptor frequently targeted by venoms, the TRPV1 receptor. TRPV1 neurons are responsible for perceiving pain, but also heat. Recall that we TRPV1 pain neurons coordinate with the immune system by stimulating an anticipatory immune response in healthy tissues that are adjacent to an area of inital pain neuron stimulation (by injury or infection). See our previous post here. Exposure to heat temporarily activates TRPV1 neurons, but after heat exposure these nociceptors enter a quiet period, where they are desensitized to further stimulation. For marine stings, relief of pain after immersion in hot water happens because of this refractory period of decreased sensitivity.

The observation that many painful conditions that can be treated with hot water has evolutionary implications. A variety of marine and terrestrial animals have defensive venoms that show evidence of convergent evolution, manipulating vertebrate pain signaling in similar ways. Venomous organisms across the tree of life have evolved chemicals that hijack pain neurons and deter predators. Defensive painful venoms evolved in nearly 3000 fish species. These venoms are enriched with substances that elicit pain, often by triggering TRPV1 neurons.

One conundrum persists: why are TRPV1 neurons desensitized to heat in the first place? It is unlikely to be a straightforward adaptation. After all, hot water on demand was unavailable for most of human evolution. Perhaps it is a happy accident that hot water works. Either way, next time you are stabbed by a stingray, you will know what to do.

Copyright © Joe Alcock MD

Categories: Uncategorized

Joe Alcock

Emergency Physician, Educator, Researcher, interested in the microbiome, evolution, and medicine

Leave a comment