Pop Quiz: Intensive care patients often have very high blood sugars. Do you think doctors should lower their blood sugar back to the normal range with insulin?

If you were wondering about this question, I have good news. The New England Journal of Medicine published a study in September 2023 that provides a partial answer. Gunst et al performed the largest trial to date of tight glycemic control for patients in the ICU. Tight glycemic control means using insulin to reduce the blood sugar to the level of a healthy fasting person, 80-110 mg/dl. The rationale for the trial, involving more than 9000 subjects, was that “hyperglycemia is common and is associated with a poor outcome” in patients receiving intensive care. This was attributed to “glucose toxicity in cells such as neurons, renal tubular cells, hepatocytes, and immune cells.”

The authors cited conflicting results among previous trials on tight glycemic control. Wrongly, I thought that this controversy had been resolved with published evidence against tight glycemic control. Others weren’t so sure, including the group responsible for this trial. Not coincidentally, this group included Greet Van den Berghe, the investigator who published an influential single center trial that supported the practice of tight glycemic control in the ICU back in 2001.

As Van den Berghe et al. commented back in 2007: “Recently, the concept that stress hyperglycemia in critically ill patients is an adaptive, beneficial response has been challenged. Two large randomized studies demonstrated that maintenance of normoglycemia with intensive insulin therapy substantially prevents morbidity and reduces mortality in these patients.”

Larger and better designed (multi-center versus single center trials) contradicted the results of the studies Van den Berghe mentioned. A NEJM paper by Brunkhorst et al in 2008 showed that tight glycemic control caused more complications with no survival benefit. This was followed by the NICE-SUGAR study that tested tight glycemic control in 6000 adult critically ill patients. NICE-SUGAR surprised many by showing that tight glycemic control increased mortality by 2.6%.

Here, Gunst and colleagues argued that another trial was necessary because (I am editorializing here) deaths in NICE-SUGAR were from hypoglycemia caused by sloppy insulin treatment. They suspected (still editorializing) that if insulin could be given precisely, without causing hypoglycemia, that the true benefits of tight glycemic control would be revealed. To that end, Gunst and colleagues introduced a computer guided insulin algorithm that they said would prevent hypoglycemia. They hoped that with that problem solved, they might finally validate Van den Berghe’s original 2001 results.

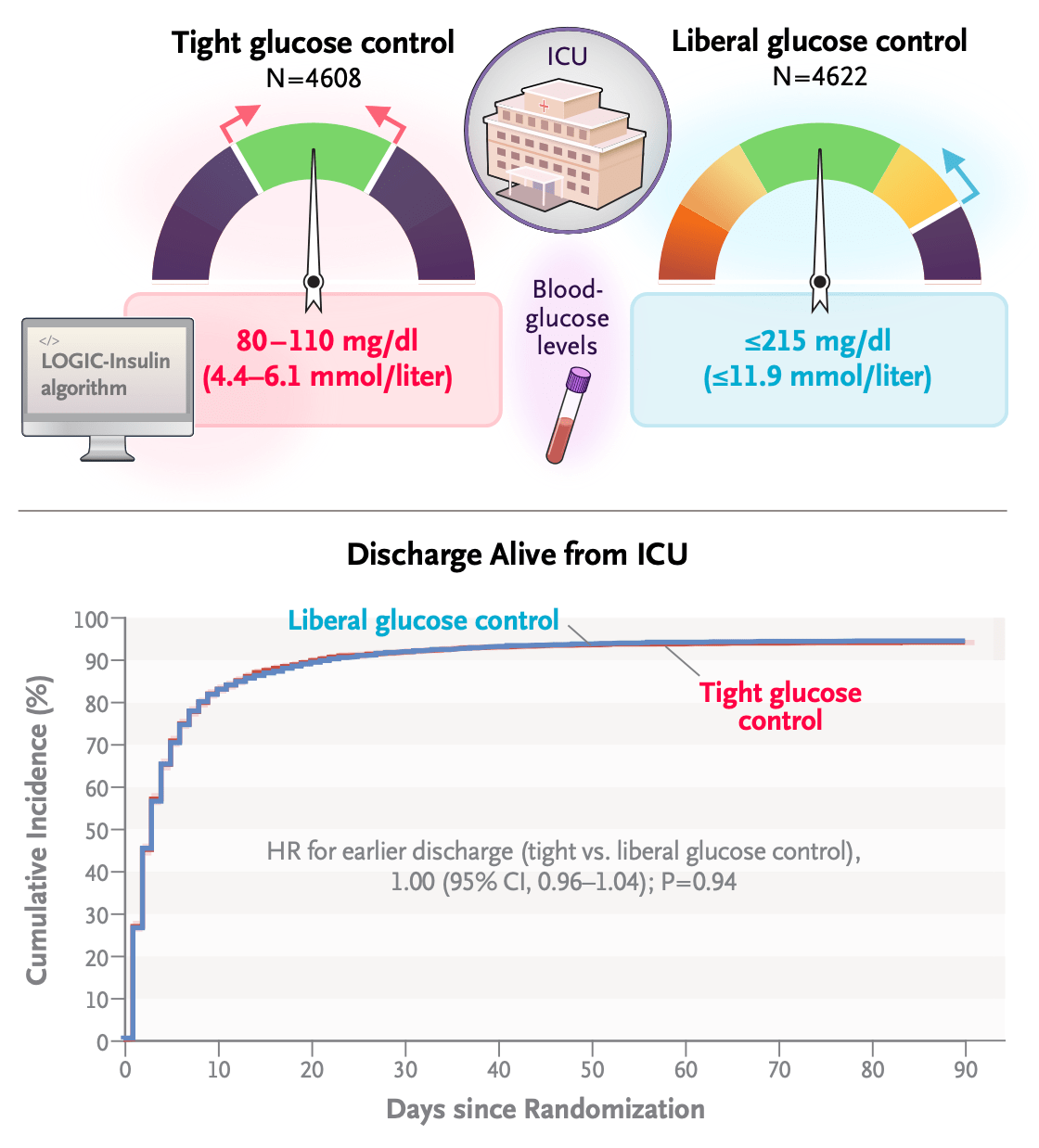

So what did they find? They did successfully prevent excess hypoglycemia with their new algorithm. The tight glucose control (intervention) and liberal glucose control (usual care) groups had similar rates of hypoglycemia, 1% and 0.7% respectively. They also did not see any differences in ICU stay or 90 day mortality. Their results are summarized in the following graphic:

It is worth noting that all patients in Gunst et al, received insulin. I am guessing this is because institutional review boards would not sanction a study in which very high glucose was left untreated. The comparison under study was aggressively intervening to normality (tight glycemic control) versus intervening less (usual care or liberal glucose control). If we consider all the multi-center randomized controlled trials of tight glycemic control, the scoreboard looks like this: Gunst et al showed no benefit and no harm, NICE-SUGAR showed significant harm, Brunkhorst et al showed no benefit and more serious adverse events, and a pediatric study by Agus et al was halted early for a signal of harm.

Together these studies should raise eyebrows. Perhaps stress hyperglycemia is indeed an “adaptive beneficial response,” that Van de Berghe dismissed back in 2007. To my knowledge there is no trial with untreated controls designed to test whether hyperglycemia is adaptive. These trials looked at the next best thing. Collectively, they show that less treatment is better than more treatment.

We should consider the alternative hypothesis that hyperglycemia is not itself protective, but the mechanism responsible for it is. Insulin resistance underlies hyperglycemia but can occur without it. Insulin resistance is an evolutionarily conserved trait that reorganizes the delivery and use of glucose energy during sickness. Because insulin treatment partially reverses insulin resistance, it also circumvents any of its potentially adaptive functions.

Either way, we should avoid the aggressive use of insulin for high blood sugar in the ER and ICU. But that conclusion is not new. After NICE-SUGAR, a 2015 study by Niven et al reported that tight glycemic control continued in medical practice without significant changes. Fewer dangerous hypoglycemia events occurred, but efforts to normalize high blood sugar continued as if NICE-SUGAR never happened. Niven et al argued for the de-adoption of dangerous and useless practices like tight glycemic control. This new paper by Gunst et al reinforces that conclusion. But this additional evidence might not be enough to course correct.

This is where an education in evolutionary medicine might help. Many in the medical community are slow to abandon entrenched views because they lack a theoretical justification for such a change. Hyperglycemia is “bad,” full stop. We have limitless esteem for “normal,” even when it is undeserved. We have a bias towards action and intervention. Medical education, practice and publication lack the training, and often, the language to recognize “beneficial adaptive responses” when they exist.

Darwin closed his opus ‘On the Origin of Species’ with the observation “there is grandeur in this view of life.” Sometimes there is grandeur in clinical trials that don’t go as expected. Studies like Gunst et al and NICE-SUGAR are not negative trials. Instead they point to a legacy of natural selection acting on the machinery governing glucose metabolism. Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance might not be as maladaptive as once feared. They might be adaptations hiding in plain sight.

Categories: Uncategorized

Joe Alcock

Emergency Physician, Educator, Researcher, interested in the microbiome, evolution, and medicine

I always wind up following multiple link rabbit holes whenever I read a new post on here. It’s almost as bad as tvtropes.com. I’ll read the new post and open links of interest in new tabs, then find other links of interest in each of those new tabs, and before I know it it’s midnight and I have 6 tabs open including an image search of “spandrels”.