Catecholamine vasopressors are used routinely in patients with sepsis to increase blood pressure and to improve blood flow to organs. However, studies have shown that high doses of catecholamines are risky. Catecholamines can lead to tachycardia, myocardial ischemia, arrhythmias, and increased myocardial oxygen demand (De Backer et al., 2012). At the tissue level, they can exacerbate tissue hypoperfusion and impair microcirculation in septic patients, potentially worsening organ dysfunction (Levy et al., 2010).

In a 2014 randomized controlled trial, Asfar and colleagues showed that higher blood pressure targets, along with the higher catecholamine doses necessary to achieve them, caused more harm than good in critically ill patients with sepsis. I wrote about that trial and the topic of catecholamines in sepsis in this previous post.

Additional work suggests that exposure to catecholamines can have adverse effects on the gut and the microbiome. Mark Lyte, a leading researcher in the field of microbiome-host interactions, showed that catecholamines serve as signaling molecules for bacteria, essentially providing a means for pathogens to sense and respond to the host’s stress signals. For example, norepinephrine has been shown to enhance the growth and virulence of pathogens, including Escherichia coli and Salmonella (Lyte, 2004).

If catecholamines are harmful, should we attempt to block their effects with beta blockers in sepsis? Beta blockers, such as esmolol, exert their effects by antagonizing beta-adrenergic receptors in the body.

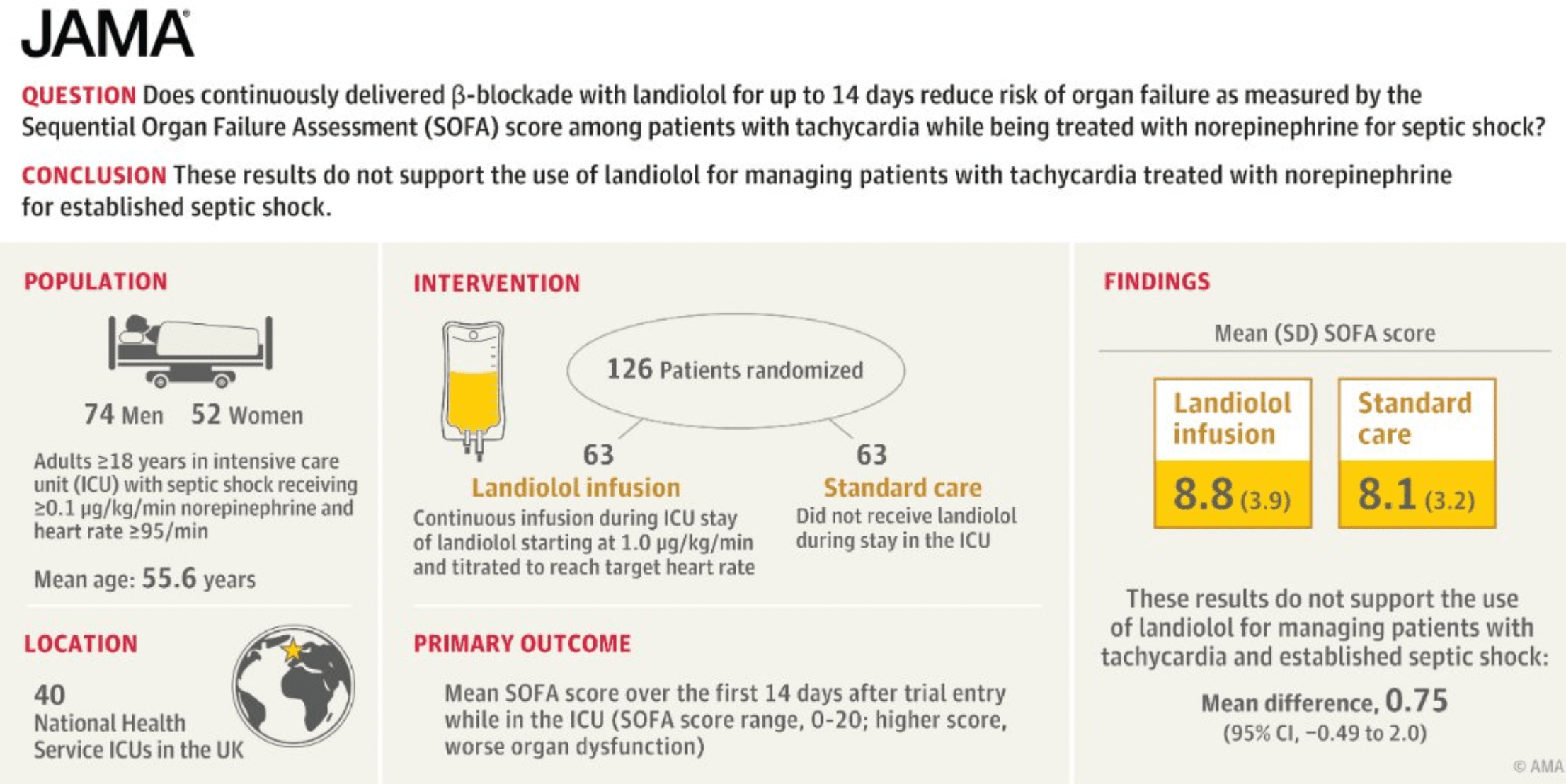

Beta blockers have the potential to mitigate several of the adverse physiological responses associated with sepsis. By reducing heart rate and myocardial contractility, beta blockers were proposed to improve myocardial oxygen supply-demand balance, decrease the risk of arrhythmias, and reduce the workload on the heart. This may be particularly beneficial in patients with sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction. A previous open label study using esmolol pointed to a survival benefit for this drug in sepsis (Morelli et al 2013). This year a randomized controlled trial tested another beta blocker, landiolol, for septic patients with tachycardia. [Of course, tachycardia is defined as a heart rate above 100; the normal resting heart rate is 60-100.]

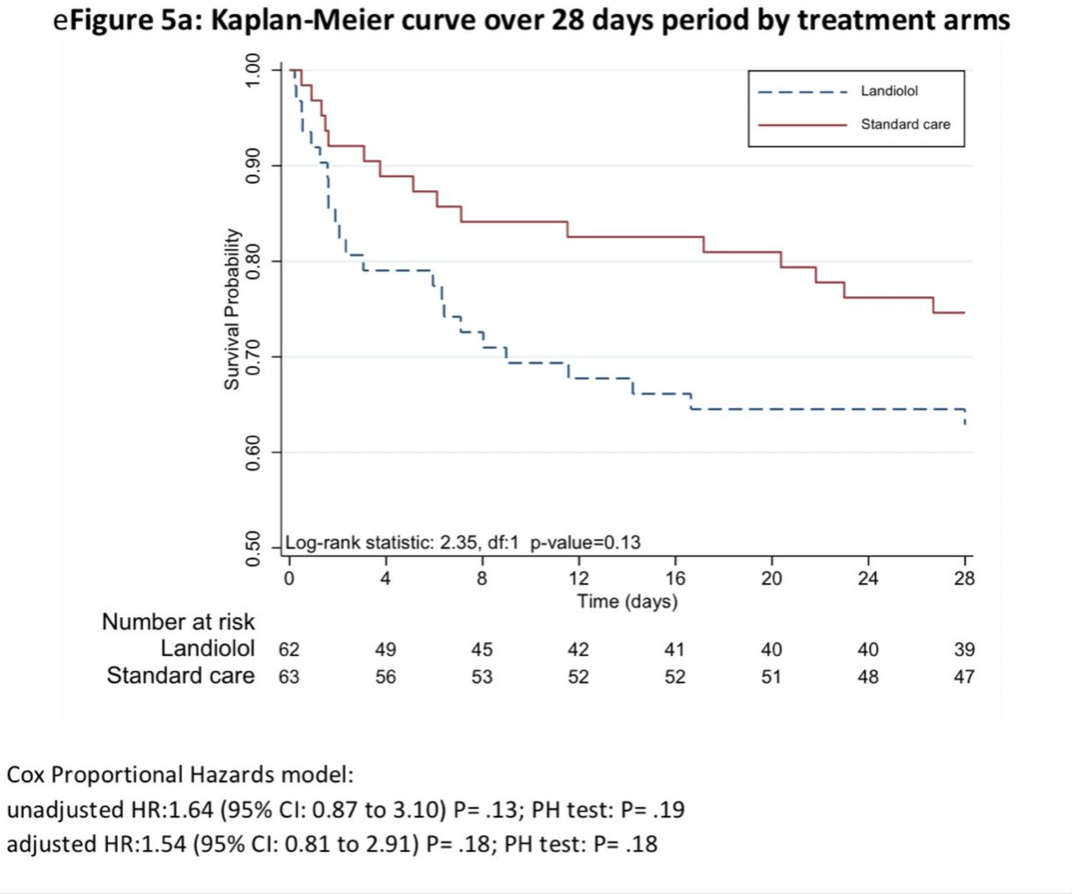

The most recent study by Whitehouse and colleagues, published in JAMA, explored whether the beta blocker landiolol might improve organ dysfunction. Survival was a secondary outcome of the study. Landiolol is a short acting beta blocker with high specificity for cardiac beta receptors. This trial intended to enroll 340 patients but was stopped early because landiolol was associated with higher mortality. More patients in the landiolol arm succumbed to sepsis: ‘Mortality at day 90 after randomization was 43.5% (27 of 62) in the landiolol group and 28.6% (18 of 63) in the standard care group (absolute difference, 15% [95% CI, −1.7% to 31.6%]; P = .08).’

Landiolol doesn’t work to reverse organ dysfunction and it certainly does not improve sepsis survival. So landiolol joins a great number of failed attempts to reverse the organ dysfunction that occurs in sepsis, as I discussed in this recent TriCEM Club EvMed presentation. As Josh Farkas wrote: Septic patients should have a bit of tachycardia. “Abnormally” high heart rates in sepsis are probably a new normal. We should not aim to “fix” tachycardia with beta blockers until new high quality evidence emerges.

Categories: Uncategorized

Joe Alcock

Emergency Physician, Educator, Researcher, interested in the microbiome, evolution, and medicine

If too much is bad and too little is bad (on average), perhaps most of the time the body’s response is functioning close to optimal for the unusual situation of a life-threatening infection.

Note also that containment of pathogens and making conditions bad for them is a host defense, so blood flow to the pathogens is best reduced to the extent they are localized. It isn’t surprising that many of the systemic responses to infection tend to reduce blood flow.

Thanks for this, Ed. I agree that regulating blood flow to infected sites is part of an effective host defense. That idea needs more attention. There is a picture that emerges from all these studies in sepsis. Host physiology changes, sometimes dramatically, from what is considered normal. Some of these abnormalities don’t cause mortality, as commonly supposed. Instead they mitigate against it. This is an argument for less is more in sepsis. Interestingly beta blockers can also block quorum sensing and virulence in pathogens. I have always advocated for interfering with the pathogen, not the host. If we can find a beta blockade that targets pathogens more than hosts, it might have some promise.